Chairman

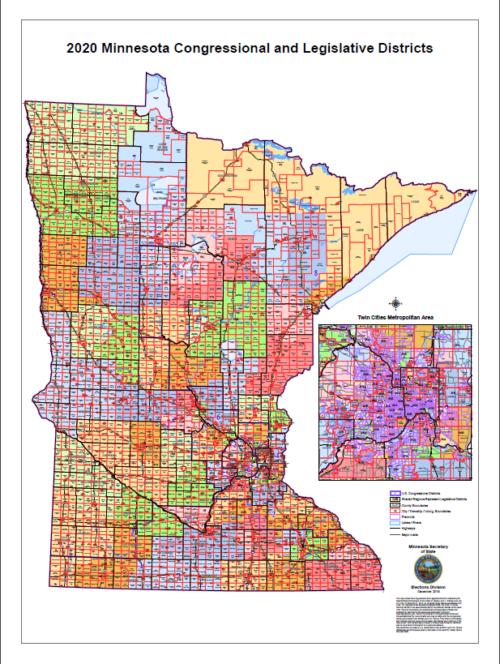

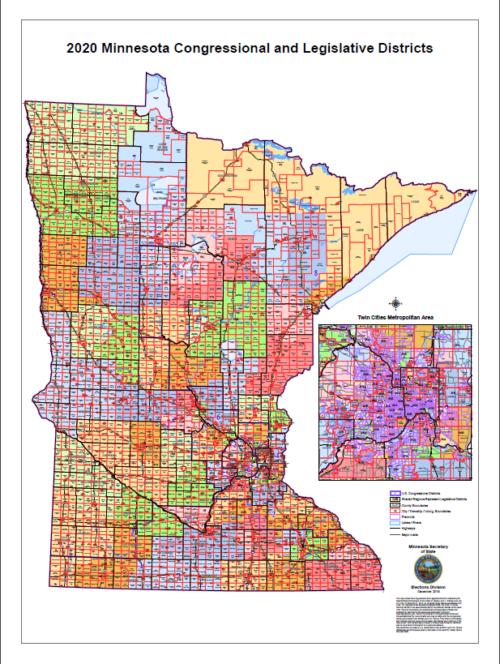

Following each decennial U.S. census, redistricting is the task of redrawing the boundaries of single-member election districts. It is necessary under the landmark 1964 Supreme Court Reynolds vs. Sims ruling (“one person, one vote”) to reconstitute the districts of representative legislative bodies (like the U.S. House, state legislature, county board, city council, etc.) to have close-to-equal populations.

Since the last redistricting, some areas’ populations have grown enormously while others have either lost population or grown relatively little (often a reality in rural communities and mature urban and suburban areas). As a result, districts which were roughly equal in population at the beginning of a 10-year cycle will show wide disparities toward the end of the decade.

While some redistricting efforts produce ludicrous outcomes (e.g., gerrymandering), legislatures and courts generally try to apply certain guiding principles to the task: creating districts which are contiguous and geographically compact, minimizing the division of political subdivisions (e.g., precincts), combining communities of similar interests, etc.

Goff Public updates straight to your inbox: Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter

What’s at stake

Forget the noble-sounding civics education description of redistricting as the equitable resetting of election districts to mirror the present population. At its most basic significance, redistricting is about the possession and retention of political power. As a result, those who are invested in the political process become obsessed with it:

- Each party hopes that they gain an edge in controlling Congress and state legislatures for the next 10 years. For example, a Democratic advantage in winning a majority in the state Senate or House can be created by heavily concentrating historically Republican-voting areas (rural and exurban areas) into as few districts as possible; other district lines would then be drawn so that areas with lots of swing voters (second- and third-ring suburbs) are paired with historically Democratic-voting areas (core cities and first-ring suburbs) to create more reliably Democratic-leaning districts.

- Interest groups hope that supporters of their causes can gain an upper hand in the elections which follow redistricting.

- Individual politicians’ careers in office are sustained or hampered in the process. As boundary lines shift, a Democrat in a “safe” Democratic district may next find themselves in a marginal one. Or two Republican incumbents may find themselves paired in the same district, leading to either one retiring in favor of the other or the two battling for the GOP nomination to represent the district.

But the course of partisan politics is not the only thing determined by the outcome of redistricting. Generational change, intra-party ideological contests, and loss or retention of the institutional wisdom among a legislative body’s members are also byproducts of a redistricting plan – all to be played out over the next 10 years.

The process

The process

In Minnesota, redistricting is the responsibility of the state legislative process… in theory. If the two houses of the legislature compromise on a plan which the governor agrees to sign into law, then the state has adopted a new redistricting plan. But in recent decades, Minnesota has experienced divided government during redistricting years (1981-82, 1991-92, 2001-02 and 2011-12). So, federal and/or state courts have ended up drawing new districts for the U.S. House and state legislature in those years (with 1992 having been bizarrely complicated!). In the process, each political party collected a group of citizen plaintiffs to file a suit with the court, pressing their ideas on constitutional grounds on how the court should draw the lines.

Eventually, after giving the legislature and governor enough time by the beginning of the election year to theoretically act (which doesn’t happen), the court issues an order imposing new election district boundaries (usually in February) – and then the mad scramble begins. Incumbents and other candidates study the new map and make personal/political decisions. Party leaders calculate their odds of winning control and (briefly) console incumbents who are unsettled by their new districts. Outside interest groups begin thinking about how they will allocate resources to help their allies win party nominations and the following election in November.

For 2022, with the current partisan-divided control of the state government, the Minnesota Supreme Court’s special redistricting panel will again be (for all practical purposes) the decision maker.

Does it really matter?

Despite an enormous amount of jockeying by political actors on the legislative and litigation fronts, from my personal experience, the partisan implications of redistricting are greatly overstated.

Neither political party will win a decided advantage over the other in the redistricting fight so long as two things occur:

- (1) a court order, which typically “plays it down the middle”

- (2) time-honored redistricting principles are applied.

I was a volunteer co-chair of the Republican redistricting litigation fundraising committees in 2001-02 and 2011-12. Just like our DFL counterparts, we raised a lot of money to support attorneys writing briefs, pleading arguments and providing maps – all necessary steps in the process, to be sure. In both decades, the court-issued plans disappointed immediate Republican hopes. Yet, in the past 20 years, Republicans have done better than they thought they might. In fact, control of the legislature has regularly seesawed between the DFL and the GOP, and Minnesota enjoys several genuinely competitive congressional seats.

Court-ordered redistricting – while not the constitutionally preferred method – has actually served Minnesotans pretty well in the recent past. It has contributed to competitive electoral results in most election cycles. And it has indirectly made divided state government more likely – something which, though lamented by some because compromise is harder to reach, has kept our state from engaging in wild swings in policymaking. All in all, this is a far healthier outcome for the body politic than exists in many other states.

So let the redistricting process unfold for what it’s worth and leave the control of Congress and the state legislature where it properly belongs: In the hands of voters, after the competitive battle of ideas.

Like what you’re reading? Discover more in our October e-newsletter here.

Share with a Friend or Colleague

Contributing Team Members

Chairman